In the history of useful accidental discoveries due to especially observant humans, vaccines have to be among the top. Roll all the way back to the year 1796. at that time, a 47 year old English scientist Edward Jenner observed that in his experience, milkmaids were immune to smallpox. Digging deeper, he discovered that the women were exposed to cowpox from the cows they milked. Subsequent to this exposure, it seemed there was a high correlation of immunity to both cowpox and smallpox. This suggested that exposure to the cowpox virus would protect one against the smallpox virus as well. A short while later, Jenner had created the first modern vaccine against smallpox, made of the pus from cowpox blisters which is credited with saving millions of lives and also paving the way for the creation of future lifesaving vaccines.

How Vaccines Work

Vaccines today still work in very much the same way as Jenner’s 1796 vaccine. Essentially, they help the vaccine recipient develop immunity by imitating an infection. By design, this type of infection almost never causes illness, but instead causes the immune system to produce T-lymphocytes and antibodies. It is possible, after getting a vaccine, that this imitation infection will cause minor symptoms, such as fever. These types of minor symptoms are normal and what we might reasonably expect as the recipient builds immunity.

Once the imitation infection goes away, the recipient is left with a supply of “memory” T-lymphocytes, as well as B-lymphocytes that will remember how to fight that disease in the future. However, it typically takes a few weeks for the body to produce T-lymphocytes and B-lymphocytes after vaccination. Therefore, it is possible that a person infected with a disease just before or just after vaccination could develop symptoms and get a disease, because the vaccine has not had enough time to provide protection.

The mechanism by which vaccines work, is well understood. So why, especially after their historical success at preventing so many deaths and so much severe illness for the last 200 years, are there so many vaccine skeptics today? What is it about human psychology that allows us to ignore the abundance of evidence which show vaccines to be both safe and effective (currently preventing two to three million deaths every year)?

How Did We Get Here With Respect to Vaccine Hesitancy?

Today’s opposition to the COVID vaccines can be traced in part to the general hesitancy about vaccines that came about as a result of the Wakefield affair. The widespread fear that vaccines increase risk of autism originated with a 1997 study by Andrew Wakefield, a British surgeon. The study suggesting that the measles, mumps, rubella (MMR) vaccine was increasing autism in British children was published in a prestigious medical journal, The Lancet.

It took twelve years after publishing the bogus study. During that time tens of thousands of parents around the world turned against the measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine because of the implied link between vaccinations and autism. Ultimately, The Lancet retracted the paper but the price we paid was . Today, the true causes of autism remain a mystery, but further discrediting the autism-vaccination link theory, several studies have now identified symptoms of autism in children well before they receive the MMR vaccine. And, even more recent research provides evidence that autism develops in utero, well before a baby is born or receives vaccinations.

In Calling the Shots: Why Parents Reject Vaccines, Jennifer Reich (University of Colorado at Denver) notes that starting in the 1970s, alternative-health movements adopted a postmodernist view and “repositioned expertise as residing within the individual.” Unfortunately, in the internet age, this view has skyrocketed “in arenas as diverse as medicine, mental health, law, education, business, and food, self-help or do-it-yourself movements encourage individuals to reject expert advice or follow it selectively.”

I have always found that Autodidacticism can be valuable. That said, it’s one thing to Google a food to see what you can find out about its impact on your blood glucose levels. It’s another thing completely to dismiss decades of studies on the benefits of vaccines because you’ve watched a couple of YouTube videos. Anti-vaccine activists frequently describe themselves as “researchers,” in an attempt to equate their scouring of the internet on behalf of their families with the work of scientists who publish in peer-reviewed journals. As I have noted before, this is not how science actually works.

That, in a nutshell, is how we’ve gotten to run of the mill vaccine hesitancy. What seems to be a mostly parent driven irrational fear of potential harm encouraged by grifters. parents not vaccinating their children is, while stupid and unforgivable, marginally understandable. So what gives with the COVID vaccine?

A Crisis Fifty Years in the Making

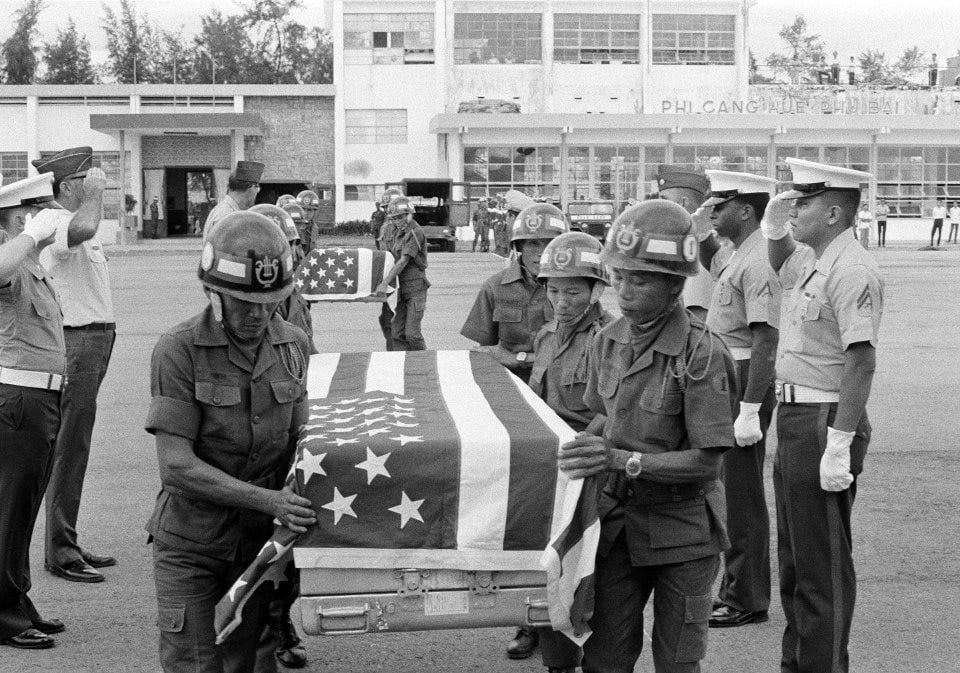

While it is true that the Trump administration managed to take mendacity to new and unparalleled heights, this is only the most extreme embodiment of a pattern that began a half-century ago. Twenty five days after I was born — Jan. 30, 1968 — a little over 65,000 Viet Cong, launched a massive invasion of South Vietnamese cities on the eve of the Tet New Year’s celebration. Known thereafter as the Tet Offensive, the maneuver led to two outcomes: (1) the Viet Cong suffered enormous troop losses; and, (2) the confidence of many Americans was smashed. In turn, many began to call into question assurances by then President Lyndon B. Johnson that the United States was actually turning the corner in Southeast Asia. Further, Americans now began to wonder about the claim that the enemy’s resources were nearly spent.

The Johnson White House had engaged in systematic deceit for years by the time the Tet Offensive occurred. Johnson had been certain that the war in Vietnam could be won in six months. He was also hesitant to rally popular support for a war that might derail his domestic policy priorities. The Johnson administration downplayed Vietnam at every critical juncture.

As it was the case that Johnson would not acknowledge that he had committed our nation to war, he was certainly not going to disclose its true cost. He buried Vietnam expenditures — which totaled roughly $5 billion (almost $39 billion in today’s dollars) — in the 1965 Pentagon budget. It would shock members of Congress when, six months later, in the middle of the fiscal year, the administration was forced to request a sizable supplementary appropriation to cover the swiftly mounting costs of the war. By 1967, even as Johnson continued to play down the budgetary implications of Vietnam, the war costs approached $26.5 billion for the fiscal year.

In economics classes they teach the concept of production possibilities frontiers in terms of a very simplified model. A society must trade off between producing guns or butter. The political realities of the moment pitJohnson’s beloved Great Society — the ambitious programs including things like Medicare and Medicaid, assistance to primary and secondary education, Head Start and nutritional assistance for struggling families and students — against the fight against global communist domination in the form of our proxy war in Vietnam. In other words, the administration found that to pay for both guns and butter was next to impossible. Worse, the wartime deficit spending had created a spiral of inflation that undermined much of the administration’s domestic policy as well as their political standing.

Whatever benefit of the doubt Americans might have been giving their president thus ended with Tet. Weeks later, CBS’s Walter Cronkite — by some estimations the most trusted man in America — famously repudiated the “optimism of the American leaders” and called into question the “silver linings they find in the darkest clouds.” Having lost Cronkite, Johnson is said to have believed that he had lost the country.

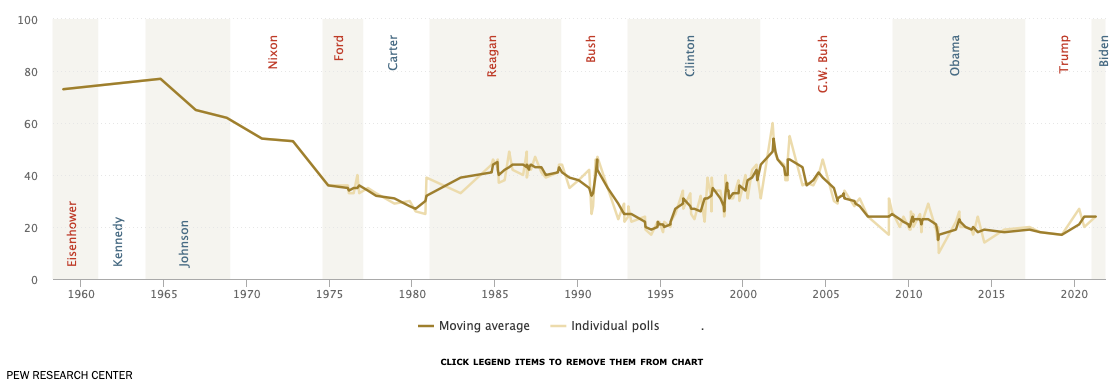

In the decades which followed, a series of economic crises and political scandals only widened the credibility gap. Nixon’s Watergate in the 1970s being the most recognizable. By the start of the 1980 election season, trust in public institutions hit record lows. In 1964, 78 percent of Americans thought that the government could be “trusted to do the right thing” either “always” or “most of the time.” By the time of Ronald Reagan’s election in 1980 that figure had plunged to 26 percent.

Reagan didn’t help matters. He was benefiting from his outsider status. After all, if government wasn’t to be trusted, shouldn’t we have less of it? Americans also grew more likely to agree that “the best government is the government that governs least.” In an April 1986 news conference, Reagan famously quipped, “the nine most terrifying words in the English language are: I'm from the Government, and I'm here to help.”

Sadly, this black and white thinking seems to have pervaded a significant segment of society. A little more than 1/2 century after the bottom fell out under Johnson, the programs that provide health care to the elderly and struggling, education programs and school meals to poor children, civil rights protections to minorities are on the chopping block. In no small part, this is because Americans have been conditioned over this same time to distrust their leaders.

Is it any wonder then, that there is so much distrust over the COVID vaccine?

Unsurprising Results

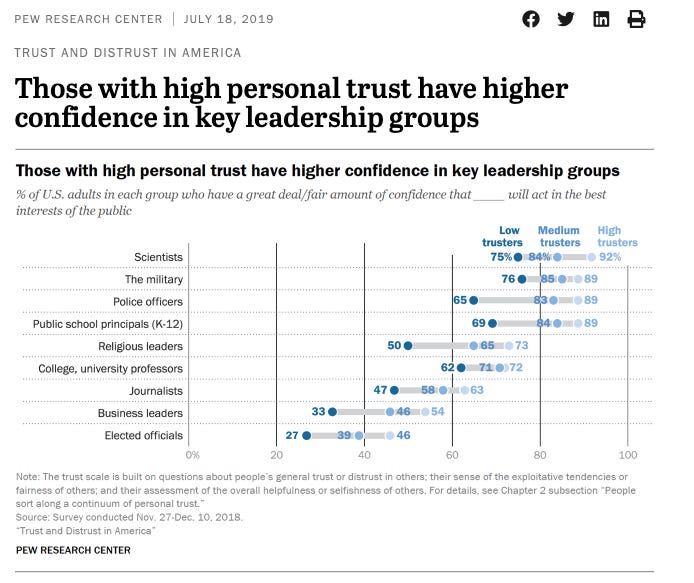

As of 6 a.m. EDT Dec. 28, a total of 205,420,745 Americans had been fully vaccinated, or 62 percent of the country's population, according to the CDC's data. When you look at the Pew Research graph above, you get a sense of how trust in general is negatively impacting COVID vaccination rates in America. That Elected officials are amongst the least trusted in America is the most disturbing. It seems that our cynicism about government has given us amnesia as to who makes up our government.

We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.

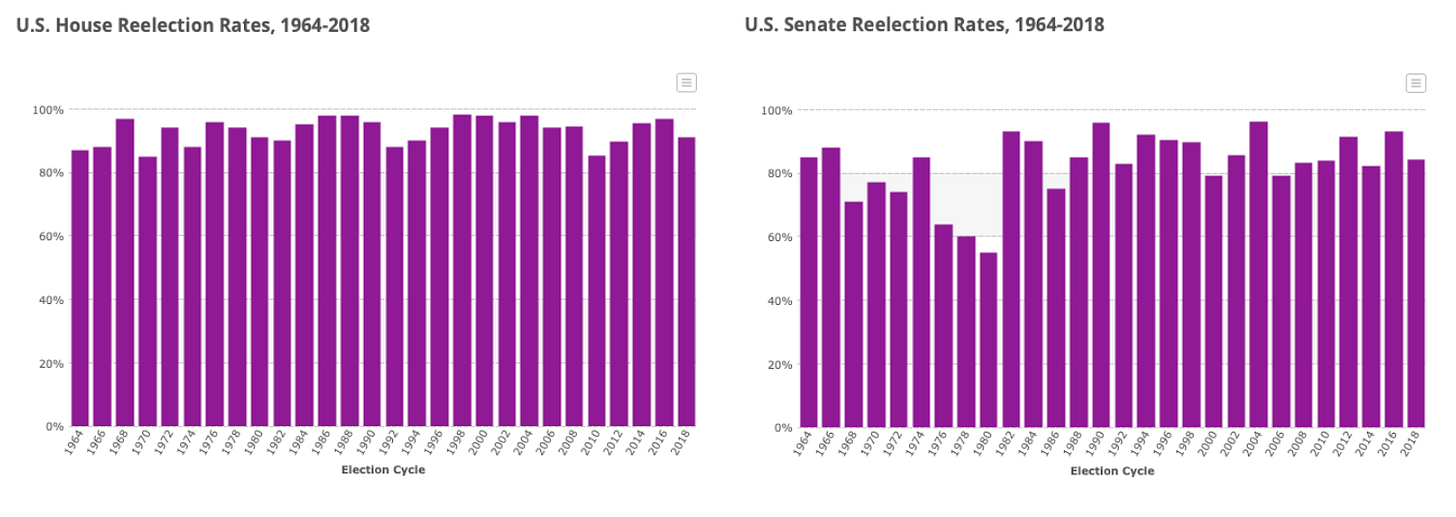

Although I have always felt this is a bit like the Education crisis in America. In the sense that polls often return interesting contradictions. People often report that other schools are below average and the school they send their child to is above average. Likewise, while there is widespread distrust in our elected officials, their reelection rates are through the roof.

While there must certainly be an explanation that squares these two data points, one thing we might try doing is being more charitable in our own thinking. I say this because the fundamental attribution error cognitive bias might be in play here. This bias causes you to judge others on your perception of their character, but yourself on the situation. It's not only kind to view others' situations with charity, it's more objective too. Be mindful to also err on the side of taking personal responsibility rather than justifying and blaming.

A New Year’s Resolution for 2022

Give people the benefit of the doubt. Assume that they had positive intentions, identify the situational details, and get the bigger picture.

Perhaps more benefit of the doubt to the unvaccinated will lead to more openness on their part as to why they would benefit from getting the jab. We need many many more people to get vaccinated and we should leave no approach untried in our efforts. Certainly this approach with your vaccine hesitant friends and family can do no more harm than is already being done by them not getting the jab.

being completely dismissive of vaccines is naive. being skeptical is a necessary requirement. interested if you are aware of this and what you think. https://www.canadiancovidcarealliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/The-COVID-19-Inoculations-More-Harm-Than-Good-REV-Dec-16-2021.pdf